The history of emergency medicine is marked by debates about best practices in resuscitation. Vascular access in cardiac arrest represents one of the oldest and most persistent of these debates. From the introduction of intraosseous (IO) access in the 1920s by Drinker and colleagues, to its renaissance in the 1980s, the emergency medical community has consistently sought to optimize drug delivery routes in critical situations.

Today, the PARAMEDIC-3 study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, brings crucial new insights to this question. This study represents the most rigorous effort to date comparing “IO-first” and “IV-first” strategies in the prehospital setting.

Historical Context

Before diving into the study details, let’s recall the historical context. IO access was first used during World War II, then largely abandoned with the advent of modern IV catheters. Its resurgence in the 1980s was primarily driven by pediatric applications before expanding to adult use. Today, some EMS systems report IO utilization rates up to 60%.

The PARAMEDIC-3 Study in Detail

Design and Methodology

This multicenter, randomized, open-label trial was conducted across 11 emergency medical systems in the United Kingdom. It presents several notable methodological characteristics:

– Population: 6,082 adult patients in prehospital cardiac arrest

– Period: November 2021 to July 2024

– Randomization: 1:1 between IO-first strategy (3,040 patients) and IV-first (3,042 patients)

– Primary outcome: 30-day survival

– Multiple secondary outcomes including neurological status

Intervention Protocol

Paramedics followed a precise protocol:

-

-

- Initial attempt according to randomization

- Maximum of two attempts with the first method

- Option to switch strategy after two failures

- Anatomical site choice left to practitioner discretion

-

Detailed Results

Primary Outcome

– IO Group: 4.5% survival at 30 days (137/3,030)

– IV Group: 5.1% survival at 30 days (155/3,034)

– Adjusted odds ratio: 0.94 (95% CI: 0.68-1.32)

Notable Secondary Outcomes

-

-

- Return of Spontaneous Circulation:

-

– IO: 36.0% (1,092/3,031)

– IV: 39.1% (1,186/3,035)

-

-

- Favorable Neurological Outcome:

-

– IO: 2.7% (80/2,994)

– IV: 2.8% (85/2,986)

-

-

- Median Time to Drug Administration:

-

– Both groups: approximately 24 minutes

Comparative Analysis with Existing Studies

The VICTOR Study: An Important Predecessor

The VICTOR study, conducted in Taiwan and recently published, provides a crucial comparison point. This study randomized 1,771 patients between humeral IO and upper limb IV access. Its main results align with PARAMEDIC-3:

– No significant difference in survival

– No reduction in drug administration time

– Similar complication rates

Meta-analyses and Observational Studies

Previous literature suggested conflicting results:

– Observational studies: tendency to show less favorable results for IO

– Potential bias: IO often used after IV failure

– Small randomized studies: heterogeneous results

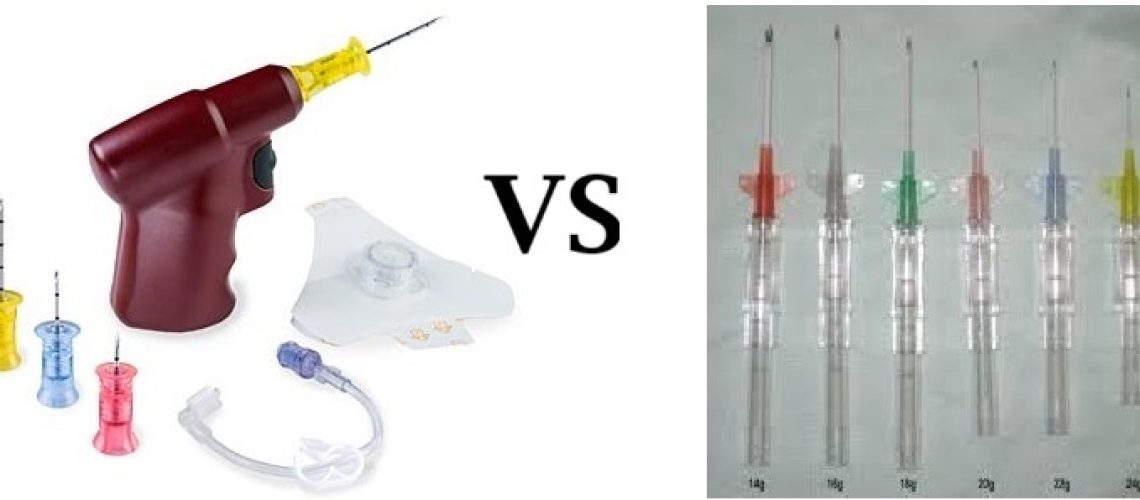

In-Depth Technical Aspects

Anatomy and Physiology

IO access presents important physiological characteristics:

-

-

- Medullary Vascularization

-

– Dense sinusoidal network

– Rapid venous drainage

– Direct connection to systemic circulation

-

-

- Insertion Sites

-

– Proximal tibia: most commonly used

– Proximal humerus: potentially faster absorption

– Other sites: distal tibia, sternum (rarely used)

Pharmacokinetic Considerations

Significant differences exist between IO and IV:

-

-

- Drug Absorption

-

– Lipophilic: possible reduced absorption in IO

– Hydrophilic: comparable absorption

– Variations by insertion site

-

-

- Plasma Peaks

-

– Humeral IO: comparable to peripheral IV

– Tibial IO: generally slower

– Potential impact on drug efficacy

Practical Implications by Region

North America

– Advanced paramedic systems

– Strong IO adoption

– Standardized protocols

– Extensive training required

Europe

-

-

- United Kingdom

-

– Autonomous paramedics

– Mixed IO/IV use

– Protocols similar to study

-

-

- Continental Europe

-

– More frequent physician presence

– Traditional preference for IV

– Variable IO adoption

Asia-Pacific

– Highly heterogeneous systems

– Variable training

– Growing IO adoption

– Variable economic constraints

Critical Analysis

Study Strengths

-

-

- Rigorous Design

-

– Appropriate randomization

– Large sample size

– Complete follow-up

– Intention-to-treat analysis

-

-

- Pragmatic Aspects

-

– Reflects real practice

– Protocol flexibility

– Multiple participating sites

Significant Limitations

-

-

- Methodological

-

– Early recruitment termination

– Impossible blinding

– Allowed crossover

– Potential biases

-

-

- Practical

-

– Lack of CPR quality data

– Practice variations between sites

– Lack of post-ROSC standardization

– Limited generalizability

-

-

- Statistical

-

– Reduced power

– Multiple analyses

– Subgroup interpretation

Clinical Practice Implications

Evidence-Based Recommendations

-

-

- Access Route Selection

-

– Consider operator expertise

– Assess intervention conditions

– Account for patient characteristics

– Anticipate difficulties

-

-

- Technique Optimization

-

– Continuous training

– Skill maintenance

– Complication monitoring

– Regular practice audit

Proposed Decision Algorithm

-

-

- Initial Assessment

-

– Venous access status

– Intervention conditions

– Available resources

– Team experience

-

-

- Strategic Choice

-

– First attempt based on expertise

– Maximum two trials

– Strategy change if failure

– Continuous reassessment

Future Perspectives

Research Directions

-

-

- Needed Studies

-

– IO site comparison

– Training impact

– Specific subgroups

– Economic aspects

-

-

- Potential Innovations

-

– New devices

– Alternative techniques

– Simulation training

– Improved monitoring

Practice Evolution

-

-

- Training

-

– Standardized programs

– High-fidelity simulation

– Continuous evaluation

– Specific certification

-

-

- Protocols

-

– Regular updates

– Local adaptation

– Evidence integration

– Contextual flexibility

Key Points to Remember

-

- Overall equivalence of approaches

- Importance of technical expertise

- Need for individualized approach

- Timing importance

- Role of continuous training

This study, despite its limitations, provides valuable data to guide our practices. It reminds us that the question isn’t so much “IO or IV?” but rather “How to optimize vascular access in each specific situation?”

Conclusion

The PARAMEDIC-3 study marks a turning point in our understanding of vascular access in prehospital cardiac arrest. While it doesn’t show IO superiority, it validates both approaches in a modern prehospital system.

Références

- Couper K, Ji C, Deakin CD, et al. A Randomized Trial of Drug Route in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. N Engl J Med. 2024. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2407780 [Étude PARAMEDIC-3 principale]

- Ko Y-C, Lin H-Y, Huang EP-C, et al. Intraosseous versus intravenous vascular access in upper extremity among adults with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: cluster randomised clinical trial (VICTOR trial). BMJ 2024;386:e079878 [Étude VICTOR]

- Perkins GD, Ji C, Deakin CD, et al. A randomized trial of epinephrine in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:711-21 [Étude PARAMEDIC-2]

- Granfeldt A, Avis SR, Lind PC, et al. Intravenous vs. intraosseous administration of drugs during cardiac arrest: a systematic review. Resuscitation 2020;149:150-7

- Reades R, Studnek JR, Vandeventer S, Garrett J. Intraosseous versus intravenous vascular access during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2011;58:509-16

- Soar J, Böttiger BW, Carli P, et al. European Resuscitation Council guidelines 2021: adult advanced life support. Resuscitation 2021;161:115-51

- Panchal AR, Bartos JA, Cabañas JG, et al. Adult basic and advanced life support: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines. Circulation 2020;142:Suppl 2:S366-S468

- Daya MR, Leroux BG, Dorian P, et al. Survival after intravenous versus intraosseous amiodarone, lidocaine, or placebo in out-of-hospital shock-refractory cardiac arrest. Circulation 2020;141:188-98

- Nolan JP, Sandroni C, Böttiger BW, et al. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine guidelines 2021: post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Med 2021;47:369-421

- Hooper A, Nolan JP, Rees N, Walker A, Perkins GD, Couper K. Drug routes in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a summary of current evidence. Resuscitation 2022;181:70-8

- Vadeyar S, Buckle A, Hooper A, et al. Trends in use of intraosseous and intravenous access in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest across English ambulance services: a registry-based, cohort study. Resuscitation 2023;191:109951

- Perkins GD, Neumar R, Hsu CH, et al. Improving outcomes after post-cardiac arrest brain injury: a scientific statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Resuscitation 2024;201:110196

- Brebner C, Asamoah-Boaheng M, Zaidel B, et al. The association of intravenous vs. humeral-intraosseous vascular access with patient outcomes in adult out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. Resuscitation 2024;202:110360

- Nishiyama C, Kiguchi T, Okubo M, et al. Three-year trends in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest across the world: second report from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR). Resuscitation 2023;186:109757